Poetry is a gift. Not one you give away forever or keep all for yourself. Poetry is a gift that you share and which grows the more it’s given. This summer, I had the chance to share poetry with 20 wonderful elementary school students at The Monarch School. My fellow Poetic Youth volunteers and I brought the paper and markers, and the students brought their courage, humor, and imagination.

Part of the gift of poetry is the community it creates. In the short time I’ve been with Poetic Youth, I’ve gotten to know the other volunteers through lesson planning, workshops, and events. Sitting down to prepare our lesson for Monarch was like sitting among good friends.

At Monarch, we started building a creative community with a simple game to stretch our imaginations. We brought in a strange-looking object, and each student took a turn pretending to be the inventor of the object and explaining what it did.

“This is my bug smasher!” one boy pronounced. His classmates must have thought this was a great idea because four more students decided they had also invented a bug smasher.

A little bit of silliness is a great way to shake up our usual routines, roles, and expectations. Games like this bring everybody in the room to the same space at the same level. Making up the use of a weird-looking object is a low-risk activity that many students feel safe enough to try. Later, when we ask them to write about themselves and what’s important to them, this communal play helps build up confidence that encourages them to take a risk and write honestly.

We played one more game — a Poetic Youth favorite — called the opposite game. Everyone stands in a circle. Someone begins by saying one thing is the opposite of another. For example, “Candy is the opposite of the moon.” The next person says, “The moon is the opposite of a minivan,” and on and on.

One of the Monarch students came up with my favorite opposite ever: “Stars are the opposite of a hairline!”

We had to ask them to repeat the word “hairline” because what second-grader has the word or concept “hairline” working in the front of their mind ready to be deployed at any time?

By the end of these two warm-ups, we had begun to create a small community where students, volunteers, and even Monarch staff were free to be silly and explore whatever idea they wished (including hairlines) in their own voice.

Poetry is also a gift of sincerity. Because poetry is permissive, neither making specific demands of readers and writers nor holding them to hard rules, it is a wonderful place to be honest. There’s no punishment for “wrong” thinking or writing, and no reward for “correct” poems. Few other endeavors afford us so much freedom to be ourselves without fear of persecution, overt or systemic. There’s no reason to read or write a poem except that you want to.

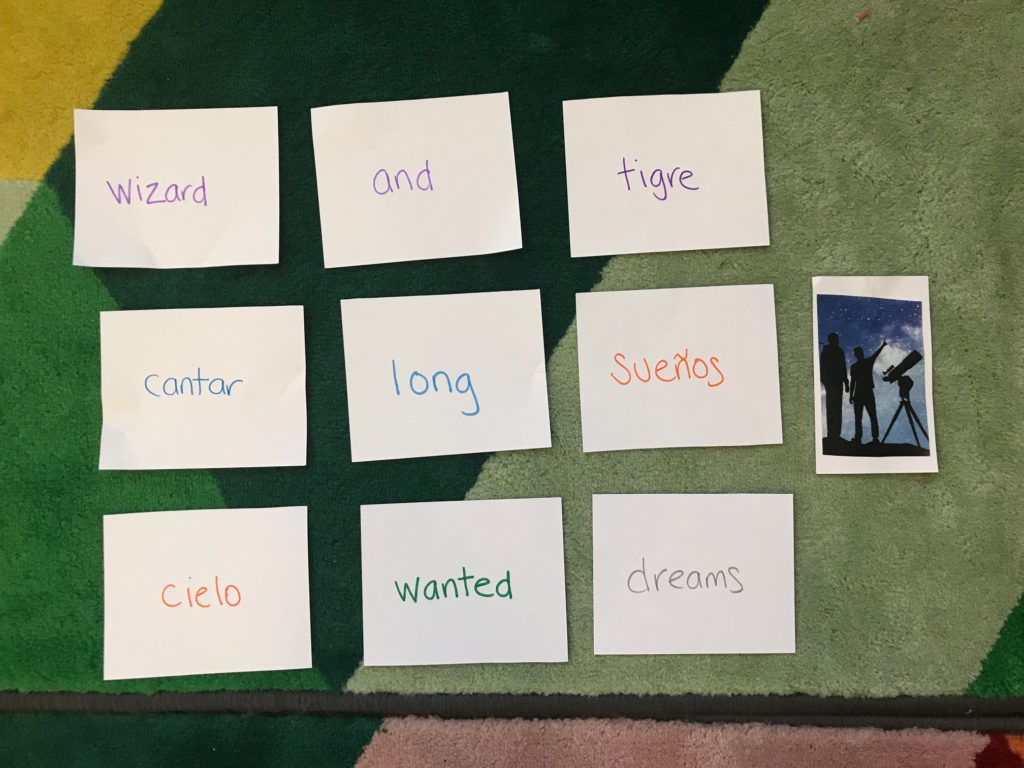

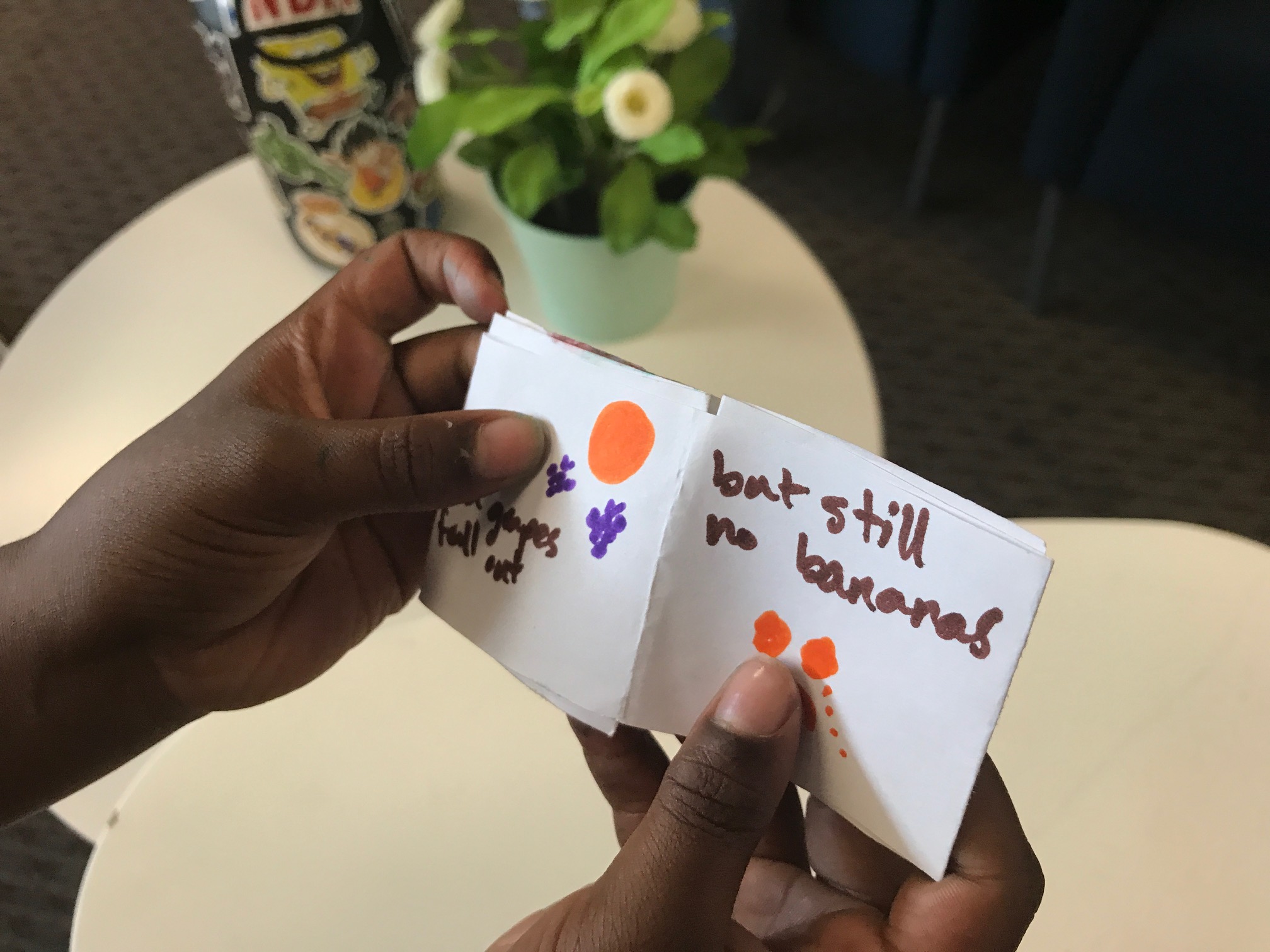

So, for our main activity, we prepared little blank books for the students to fill with whatever was important to them that day. To get everyone started, we asked the students what makes a book a book. The class showed off their knowledge of books and stories by shouting out elements including characters, plot, setting, and even covers, pages, and spines.

“You’re going to write a book today! To help us get started, let’s pick a few of these elements for our book. How about characters? Who is your book going to be about?” we prompted.

“Zordon!” one of the older kids called out immediately.

We went on collecting setting and plot ideas for Zordon’s world. Students who wished could use this as a prompt, or they could choose to write about anything else they wanted. Although most students set to work with enthusiasm, one little boy sat in a chair facing the wall, chanting something to himself.

“What would you like to write about?” I asked.

The boy kept repeating, “My life sucks. My life sucks. My life sucks.”

The students at The Monarch School are all impacted by homelessness. This, along with all the challenges of growing up, gives a child plenty of reasons why he might say his life sucks. Whatever the reason, today that is what this boy had on his mind.

In the spirit of being honest, I asked, “Okay, why does your life suck? Maybe you want to write about that?”

“I don’t have any friends,” he said.

Thinking that sounded like a story worth writing, I gently encouraged the boy to write and draw. When he finally agreed to pick up a blue marker, I floated around the room to see how the other students were doing. A few minutes later, the boy came up to me to tell me that he’d finished.

“Do you want me to read your story?” I asked. He thought about it and decided to let me read. A boy had no friends. Then, he went to play soccer and made some friends. Later, he lost those friends, too.

Life is not only composed of happy endings. Those sad but real endings, like having no friends, take courage to write. Poetry is a place where even sad stories can be appreciated and understood. This is one reason why I think it’s especially important that we expose children facing extraordinary challenges to creative writing and the arts. The page can be a safe and productive place to contend with life’s struggles.

Soon it was time for my favorite part of writing poetry: sharing. We heard stories about Zordon fighting aliens, little boys without friends, climbing rainbows, and even Batman fan fiction featuring cameos by the Monarch School staff.

I leave these workshops in gratitude and peace. The enthusiasm, creativity, and honesty of young people is humbling. There is so much to learn from them. Serenity comes from being a small part of something much larger and more powerful than I am — this growing gift of poetry that we share.